Trabajo, educación y cultura

Alberto Buela (*)

Trabajo

Suele recomendarse en filosofía, así lo han hecho, entre otros, Heidegger, Zubiri, Bollnow y nuestro Wagner de Reyna, que la primera aproximación al objeto de estudio sea a través de un acercamiento etimológico. Porque, como afirma Heidegger: “el lenguaje empieza y termina por hacernos señas de la esencia de una cosa”[1]. Así comprobamos que trabajo proviene del verbo latino tripaliare que a su vez proviene de tripalium= tres palos, que era un cepo o yugo hecho con tres palos donde se ataban los bueyes y también a los esclavos para azotar. Vemos como la aproximación etimológica a término trabajo nos revela su vinculación al sufrir, a cualquier actividad que produce dolor en el cuerpo. De ahí que el verbo tripaliare significa en latín atormentar, causar dolor, torturar.

Aclarado el término pasemos ahora a su descripción fenomenológica. El trabajo, que puede ser definido como la ejecución de tareas que implican un esfuerzo físico o mental para la producción de algún tipo de bienes o servicios para atender las necesidades de los hombres, tiene dos manifestaciones: como opus= obra y como labor=labor. En tanto que obra expresa el producto o bien objetivo que produce, mientras que como labor expresa el producto subjetivo que logra.

Sobre la obra no hay discusión, la obra está ahí, al alcance de la mano y de la vista, a lo sumo puede discutirse si ésta está bien o mal hecha. El asunto se complica en el trabajo como labor, pues implica una subjetividad, la del trabajador. Pues en la labor está implicada la expresión del propio trabajador. Hasta no hace mucho se reservaba el término de “labores” a una materia en los colegios de señoritas. Creo que la materia se denominaba “manualidades y labores”, donde hilado, el bordado, el tejido y la costura constituían su temática. Es que el trabajo como labor implica la formación profunda del hombre que trabaja. No es necesario aclarar que el término hombre comprende tanto a la mujer como al varón, pues ambos forman parte del género hombre. La lengua alemana posee también dos términos para designar las manifestaciones del trabajo: Arbeit para obra y Bildung para labor. Y este último tiene el sentido de formación.

Y acá es donde encontramos nosotros la vinculación entre el trabajo y la escuela: en la búsqueda no tanto de la información, de conocimientos sino en la búsqueda de la formación del educando.

Y a esto sobre todo ayuda el trabajo en una época tan desacralizada como la que hoy nos toca vivir, pues lo sagrado desapareció de nuestra conciencia habitual. Y la educación en los valores morales se ha hecho muy difícil, teniendo en cuenta que lo que el niño ve a diario es corrupción, crímenes, asesinatos, robos, golpizas, droga, desorden, anomia, etc.

Así el trabajo es el único medio que tenemos a mano para crear virtud[2], al menos por la repetición de actos, de levantarnos todos los días temprano aunque no nos guste. De lavarnos la cara y peinarnos. A cumplir un horario. De tener que escuchar al compañero de trabajo con sus diferencias y acostumbrarnos a convivir con el otro, aunque más no sea por ocho o seis horas diarias. El trabajo limita y morigera el capricho subjetivo, de donde nacen todas nuestras arbitrariedades y nuestros males.

Y como la virtud se funda en la repetición habitual de actos buenos, el trabajo nos permite el paso inicial a la virtud, que es hacer las cosas bien, correctamente, evitando el daño al otro y al medio ambiente.

En nuestro país hemos tenido el privilegio de proclamar que existe una sola clase de hombre: el que trabaja. U otro: gobernar es crear trabajo. Incluso la máxima obra teórico-política que con rasgos propios y originales se realizó en Argentina durante el siglo XX fue la Constitución del Chaco de 1951, donde en su preámbulo afirma: Nosotros el pueblo trabajador….y no como las Constituciones de1853, incluso la de 1949 y la actual de 1994: Nosotros el pueblo…al típico estilo liberal, hijo de los juristas de la Revolución Francesa.

Es que en una época no tan lejana se sostuvo y se proclamó a los cuatro vientos el ideal de la liberación por el trabajo y a través de él, el ahorro. Es que el salario justo es aquel que permite hacer frente a la necesidad de consumo más un plus para el ahorro.

Hoy, por el contrario, el no trabajo y el subsidio han venido a reemplazar el ideal de la liberación por el trabajo. Esperemos que no sea para siempre y podamos retomar tan loable ideal.

Educación

Como hicimos con el término trabajo, observamos que educación viene del latín ducere que significa guiar, conducir. De modo que educar consiste en poder guiar conducir al educando al logro de su formación de hombre como tal.

Este ideal educativo nos viene desde los griegos con su famosa paidéia, que significó la formación del hombre de acuerdo con su auténtico ser; el de la humanitas romana de Varrón y Cicerón, de educar al hombre de acuerdo con su verdadera forma humana; el del mundo cristiano con su idea de ejemplaridad en todos los tratados De Magistro de los pensadores medievales que tienen a Cristo como maestro de los maestros y el del mundo moderno con Johann Pestalozzi y su método.

Todo este ideal educativo se plasmó en nuestro país a partir de la ley 1420 por la cual la educación primaria tiene como objeto la eliminación del analfabetismo y la formación en el niño de los valores morales. (Se enseñan modos, maneras, costumbres. En una palabra, se enseñan hábitos prácticos etc.)

De igual manera la educación media tiene por objeto fortalecer la conciencia de pertenencia histórico-política a la Nación a que se pertenece. (Se enseñan valores ciudadanos y patrios. En una palabra hábitos socio-políticos)

Y finalmente la educación superior que tiene por objeto entregar un método de estudio sistemático y reconocido, en donde los logros de los niveles previos se puedan expresar y se detecten las carencias.

Todo este ideal educativo se cuestionó a partir del último cuarto del siglo XX cuando masivamente la escuela dejó sus ideales de formación para limitarse, en el mejor de los caso, ha ser una simple transmisora de conocimientos.

La escuela, y hay que recordarlo una vez más, como su nombre lo indica es y debe ser antes que nada el lugar del ocio. El término viene del latino schola, el que a su vez viene del griego scolh(scholé) que significa ocio. Antes que cualquier otra cosa, la escuela es el lugar del ocio. Si se quiere, el lugar donde no se hace nada. Nada de útil, nada que no tenga su fin en sí mismo. Nada en vista a otra cosa que no sea la formación del propio educando. El carácter de útil, la utilidad, viene después de la escuela y es en general una preocupación de los padres. Una vez que se terminó la escuela se verá si sus enseñanzas son útiles. Pero la escuela no es otra cosa que el lugar para aprender en el ocio. Es el disfrutar jugando en el aprendizaje, un aprendizaje que vale por sí mismo y no en vista a otra cosa. Este aprender es por nada. Tiene un fin en sí mismo que es el acceso al saber y la sabiduría.

Hace 2500 años Platón en la Carta VII nos legó una enseñanza perdurable de cómo aproximarnos al saber y la sabiduría: primero a través del nombre, luego buscando la definición, en tercer lugar la imagen representada para llegar por último al conocimiento mismo. Y para que se entienda pone el ejemplo del círculo. En primer lugar tenemos un nombre llamado círculo, luego buscamos la definición compuesta de nombres y predicados: aquello cuyos extremos distan todos igual del centro. En tercer lugar la imagen como representación sensible, copia imperfecta y no permanente ejemplificada por círculos y ruedas. Para llegar finalmente al conocimiento mismo, todo ello “después de una larga convivencia con el problema y después de haber intimado con él, de repente, como la luz que salta de la chispa, surge la verdad en el alma[3]

Cultura

Cada vez que escuchamos hablar de cultura o de gente culta, asociamos la idea con la gente que sabe mucho, que tiene títulos, que es léida, como decían nuestros padres, allá lejos y hace tiempo. Es por eso que ha hecho fama, a pesar de su demonización política, la frase de Goebbels: Cada vez que me hablan de cultura llevo la mano a mi revólver. Porque sintetiza mejor que nadie, en un brevísimo juicio, el rechazo del hombre común, del hombre del pueblo llano, al monopolio de la cultura que desde la época del Iluminismo para acá poseen y ejercen los ilustrados y sus academias.

Cultivo

En cambio para nosotros cultura es el hombre manifestándose. Es todo aquello que él hace sobre la naturaleza para que ésta le otorgue lo que de suyo y espontáneamente no le da. Es por ello que el fundamento último de lo que es cultura, como su nombre lo indica, es el cultivo.

Cultura es tanto la obra del escultor sobre la piedra amorfa, como la obra del tornero sobre el hierro bruto o como la de la madre sobre la manualidad del niño, cuando le enseña a tomar el cubierto.

Vemos de entrada nomás, como esta concepción es diametralmente opuesta a esa noción libresca y académica que mencionamos al comienzo.

El término cultura proviene del verbo latino colo/cultum que significa cultivar.

Para el padre de los poetas latinos, Virgilio, la cultura está vinculada al genius loci (lo nacido de la tierra en un lugar determinado) y él le otorgaba tres rasgos fundamentales: clima, suelo y paisaje.

Caracterizado así el genius loci de un pueblo, éste podía compartir con otros el clima y el paisaje pero no el suelo. Así como nosotros los argentinos compartimos el clima y paisaje con nuestros vecinos pero no compartimos el suelo. Y ello no sólo porque sea éste último donde se asienta el Estado-Nación sino, desde la perspectiva de Virgilio el suelo es para ser cultivado por el pueblo sobre el se asienta para conservar su propia vida y producir su propia cultura.

Enraizamiento

Pero para que un cultivo fructifique, éste debe echar buenas raíces, profundas y vigorosas que den savia a lo plantado. Toda cultura genuina exige un arraigo como lo exige toda planta para crecer lozana y fuerte, y en este sentido recordemos aquí a Simone Weil, la más original filósofa del siglo XX, cuando en su libro L´Enracinement nos dice: el reconocimiento de la humanidad del otro, este compromiso con el otro, sólo se hace efectivo si se tienen “raíces”, sentimiento de cohesión que arraiga a las personas a una comunidad”[4]. La filósofa ha dado un paso más, pues, pasó del mero echar raíces al arraigo que siempre indica una pertenencia a una comunidad en un lugar determinado.

El arraigo, a diferencia del terruño que es el trozo de tierra natal, abarca la totalidad de las referencias a la vida que nos son familiares y habituales. El arraigo genuino se expresa en un ethos nacional.

Fruto

Luego de haber arado, rastreado, sembrado, regado y esperado el madurar, aparece lo mejor que da el suelo: el fruto, que cuando es acabado, cuando está maduro, es decir perfecto, decimos que el fruto expresa plenamente la labor y entonces, nos gusta.

Sabor

Y aquí aparece una de esas paradojas del lenguaje que nos dejan pensando acerca del intrincado maridaje entre las palabras y las cosas. Nosotros aun usamos para expresar el gusto o el placer que nos produce un fruto o una comida una vieja expresión en castellano: el fruto nos “sabe bien”. Y saber proviene del latín sapio, y sapio significa sabor. De modo tal que podemos concluir que hombre culto no es aquel que sabe muchas cosas sino el que saborea las cosas de la vida.

Sapiente

Existe para expresar este saber un término que es el de sapiente, que nos indica, no sólo al hombre sabio, sino a aquel que une en sí mismo sabiduría más experiencia por el conocimiento de sus raíces y la pertenencia a su medio[5]. Los antiguos griegos tenían una palabra para expresar este concepto: jronhsiV (phrónesis)

Vemos, entonces, como la cultura no es algo exterior sino que es un hacerse y un manifestarse uno mismo. Por otra parte la cultura, para nosotros argentinos, tiene que americanizarse, pero esto no se entiende si se concibe la cultura como algo exterior. Como una simple imitación de lo que viene de afuera, del extranjero.

No hay que olvidar que detrás de toda cultura auténtica está siempre el suelo. Que como decía nuestro maestro y amigo el filósofo Rodolfo Kusch: “El simboliza el margen de arraigo que toda cultura debe tener. Es por eso que uno pertenece a una cultura y recurre a ella en los momentos críticos para arraigarse y sentir que está con una parte de su ser prendido al suelo”[6]

Cultura y dialéctica

Es sabido desde Hegel para acá, que el concepto es “lo que existe haciéndose”, que para él, encuentra su expresión acabada en la dialéctica, que tiene tres momentos: el suprimir, el conservar y el superar. Y no la vulgar versión de tesis, antítesis y síntesis a que no tienen acostumbrados los manuales. Hemos visto hasta ahora como la cultura pone fin, hace cesar la insondable oquedad de la naturaleza prístina con el cultivo, la piedra o el campo bruto, por ejemplo, y en un segundo momento conserva y retiene para sí el sabor y el saber de sus frutos, vgr.: las obras de arte. Falta aún describir el tercero de los momentos de esta Aufhebung o dialéctica.[7]

Si bien podemos, en una versión sociológica, entender la cultura como el hombre manifestándose, “la cultura, afirmamos en un viejo trabajo, no es sólo la expresión del hombre manifestándose, sino que también involucra la transformación del hombre a través de su propia manifestación”[8].

El hombre no sólo se expresa a través de sus obras sino que sus obras, finalmente, lo transforman a él mismo. Así en la medida que pasa el tiempo el campesino se mimetiza con su medio, el obrero con su trabajo, el artista con su obra.

Esta es la razón última, en nuestra opinión, por la cual el trabajo debe ser expresión de la persona humana, porque de lo contrario el trabajador pierde su ser en la cosas. El trabajo deviene trabajo enajenado. Y es por esto, por un problema eminentemente cultural, que los gobiernos deben privilegiar y defender como primera meta y objetivo: el trabajo digno.

Esta imbricación entre el hombre y sus productos en donde en un primer momento aquél quita lo que sobra de la piedra dura o el hierro amorfo para darle la forma preconcebida o si se quiere, para desocultar la forma, y, en un segundo momento se goza en su producto, para, finalmente, ser transformado, él mismo, como consecuencia de esa delectación, de ese sabor que es, como hemos visto, un saber. Ese saber gozado, experimentado, es el que crea la cultura genuina.

Así la secuencia cultura, cultivo, enraizamiento, fruto, sabor, sapiencia y cultura describe ese círculo hermenéutico de la idea de cultura.

Círculo que se alimenta dialécticamente en este hacerse permanente que es la vida, en donde comprendemos lo más evidente cuando llegamos a barruntar lo más profundo: que el ser es lo que es, más lo que puede ser.

Resumiendo, hemos visto como el trabajo genera virtud, al menos mundana o no trascendente, que se relaciona con la educación en tanto ambas actividades buscan la formación del hombre en su ser, para que éste pueda plasmar en su vida una cultura genuina, esto es, vinculada a su arraigo.

(*) arkegueta, aprendiz constante

buela.alberto@gmail.com

buela.alberto@gmail.com

www.disenso.info

[1] Heidegger, Martín: Poéticamente habita el hombre, Rosario, Ed. E.L.V., 1980, p. 20.-

[2] Otro gran iniciador laico, en algunas virtudes, es el deporte.

[3] Platón: Carta VII, 341 c 4. También en Banquete 210 e

[4] Weil, Simone: Echar Raíces, Barcelona, Trotta, 1996, p. 123.-

[5] Buela, Alberto: Traducción y comentario del Protréptico de Aristóteles, Bs.As., Ed. Cultura et labor, 1984, pp. 9 y 21. “Hemos optado por traducir phronimós por sapiente y phrónesis por sapiencia, por dos motivos. Primero porque nuestra menospreciada lengua castellana es la única de las lenguas modernas que, sin forzarla, así lo permite. Y, segundo, porque dado que la noción de phrónesis implica la identidad entre el conocimiento teórico y la conducta práctica, el traducirla por “sabiduría” a secas, tal como se ha hecho habitualmente, es mutilar parte de la noción, teniendo en cuenta que la sabiduría implica antes que nada un conocimiento teórico”.

[6] Kusch, Rodolfo: Geocultura del hombre americano, Bs.As. Ed. F.G.C., 1976, p.74.

[7] Buela, Alberto: Hegel: Derecho, moral y Estado, Bs.As. Ed. Cultura et Labor- Depalma, 1985, p. 61 “En una suscinta aproximación podemos decir que Hegel expresa el conceto de dialéctica a través del término alemán Aufhebung o Aufheben sein que significa tanto suprimir, conservar como superar. La palabra tiene en alemán un doble sentido: significa tanto la idea de conservar, mantener como al mismo tiempo la de hacer cesar, poner fin. Claro está, que estos dos sentidos implican un tercero que es el resultado de la interacción de ambos, cual es el de superar o elevar. De ahí que la fórmula común y escolástica para explicar la dialéctica sea la de: negación de la negación”.

[8] Buela, Alberto: Aportes al pensamiento nacional, Bs.As., Ed. Cultura et labor, 1987, p.44.-

Le nouveau président vénézuélien désavoua rapidement ce nationaliste-révolutionnaire péroniste et anti-atlantiste radical et le fit expulser dès 1999. Les idées tercéristes de Ceresole indisposaient les nombreux progressistes gravitant autour d’Hugo Chavez. Si celui-ci appliqua en diplomatie une conception assez proche des idées de Ceresole (hostilité aux États-Unis et au libéralisme prédateur, pan-américanisme institutionnel, rapprochement avec la Russie, l’Iran, le Bélarus et la Chine, soutien au Hezbollah et à la cause palestinienne), il gâcha tous ces atouts en politique intérieure comme l’avait prévenu dès 2007 Raul Baduel, son vieux frère d’arme entré ensuite dans un « chavisme d’opposition » et longtemps incarcéré.

Le nouveau président vénézuélien désavoua rapidement ce nationaliste-révolutionnaire péroniste et anti-atlantiste radical et le fit expulser dès 1999. Les idées tercéristes de Ceresole indisposaient les nombreux progressistes gravitant autour d’Hugo Chavez. Si celui-ci appliqua en diplomatie une conception assez proche des idées de Ceresole (hostilité aux États-Unis et au libéralisme prédateur, pan-américanisme institutionnel, rapprochement avec la Russie, l’Iran, le Bélarus et la Chine, soutien au Hezbollah et à la cause palestinienne), il gâcha tous ces atouts en politique intérieure comme l’avait prévenu dès 2007 Raul Baduel, son vieux frère d’arme entré ensuite dans un « chavisme d’opposition » et longtemps incarcéré.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

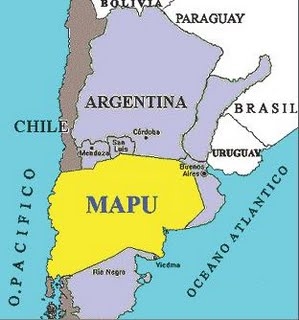

Les ennemis des Mapuches sont les politiques qui gèrent ces territoires et les congrégations multinationales qui exploitent pétrole, électricité, mines, tourisme. On citera Benetton, propriétaire de 900.000 ha dans les provinces de Rio Negro, Chubut et Santa Cruz ; Joe Lewis, ex-propriétaire de la chaîne Hard Rock ; Ted Turner, Georges Soros, Perez Companc, Amalita Lacroze de Fortabat, etc.

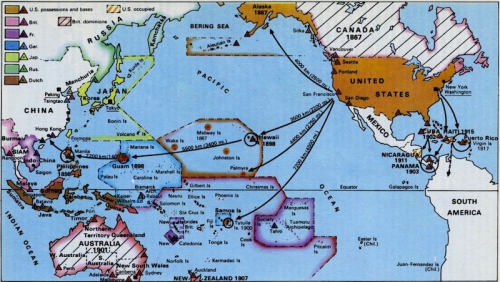

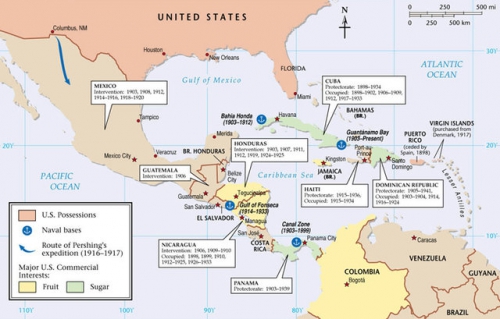

Les ennemis des Mapuches sont les politiques qui gèrent ces territoires et les congrégations multinationales qui exploitent pétrole, électricité, mines, tourisme. On citera Benetton, propriétaire de 900.000 ha dans les provinces de Rio Negro, Chubut et Santa Cruz ; Joe Lewis, ex-propriétaire de la chaîne Hard Rock ; Ted Turner, Georges Soros, Perez Companc, Amalita Lacroze de Fortabat, etc. Les Etats-Unis ont mis en place des bases militaires et déployé des troupes dans toute l'Amérique Latine. Elles dépendent du Southern Command. www.southcom.mil/ De son côté la 4e flotte patrouille dans toutes les eaux avoisinantes. Y préparent-ils une guerre de grande ampleur? Veulent-ils occuper des territoires? Le gouvernement a toujours répondu que ces forces étaient là pour combattre des terroristes ou des narco-trafiquants.

Les Etats-Unis ont mis en place des bases militaires et déployé des troupes dans toute l'Amérique Latine. Elles dépendent du Southern Command. www.southcom.mil/ De son côté la 4e flotte patrouille dans toutes les eaux avoisinantes. Y préparent-ils une guerre de grande ampleur? Veulent-ils occuper des territoires? Le gouvernement a toujours répondu que ces forces étaient là pour combattre des terroristes ou des narco-trafiquants.

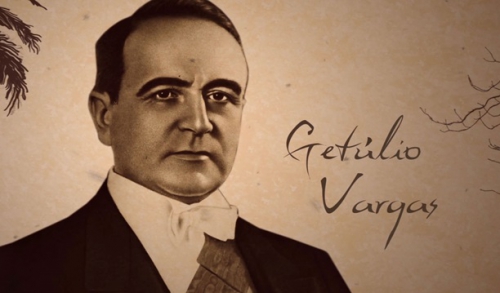

Dans la nuit du 22 août 1942, les torpilles d’un sous-marin allemand envoient au fond de la mer cinq vapeurs brésiliens patrouillant le long des côtes. Il y a 610 morts. Quelques heures après ce terrible incident, le Brésil déclare la guerre à l’Allemagne et à l’Italie. Le parallèle avec la première guerre mondiale saute aux yeux. A cette époque-là, en 1917, le torpillage de navires civils, dont le navire amiral de la flotte commerciale brésilienne, le Paranà, par des sous-marins de Guillaume II, fut aussi considéré comme un casus belli par le Brésil.

Dans la nuit du 22 août 1942, les torpilles d’un sous-marin allemand envoient au fond de la mer cinq vapeurs brésiliens patrouillant le long des côtes. Il y a 610 morts. Quelques heures après ce terrible incident, le Brésil déclare la guerre à l’Allemagne et à l’Italie. Le parallèle avec la première guerre mondiale saute aux yeux. A cette époque-là, en 1917, le torpillage de navires civils, dont le navire amiral de la flotte commerciale brésilienne, le Paranà, par des sous-marins de Guillaume II, fut aussi considéré comme un casus belli par le Brésil.

Le général Smedley Butler, auteur du livre "War is a Racket"

Le général Smedley Butler, auteur du livre "War is a Racket"